Sometimes I like to dig deeply into some x86 Windows executables files so that I can better understand how certain pieces of software work. I decided to collect here some of the things I learned and what I think is worth noting.

Here's what I'll be talking about:

- Reverse engineering a proprietary (and very weak) encryption mechanism

- Patching a binary

- Curious aspects

1. Reverse engineering a proprietary (and very weak) encryption mechanism

As part of a personal project I am working on, I had the need to access data stored in some binary files. Unfortunately, the format of those files is proprietary and almost no useful information is available online: I was basically alone in the reverse engineering of the file format.

First I disassembled, decompiled and analyzed the official DLL that is used to create and access the binary files. After a few days of headaches and guesses, I managed to collect enough information to correctly dump the data out of the file, which is organized in a data structure very similar to a B-Tree. This must have been decided in order to allow indexed random access to the data records.

In addition to simple index data storage, the file format allows for data encryption, on a record base. The naive encryption method that the engineers who designed the file format put in place made me smile, at first.

Then, I started thinking about those companies that rely on securing the data using the built-in encryption mechanism found here.

I'll now explain how the encryption works starting from the disassembly code and then I'll demonstrate how easy it is to simply do a bruteforce attack and decrypt the data.

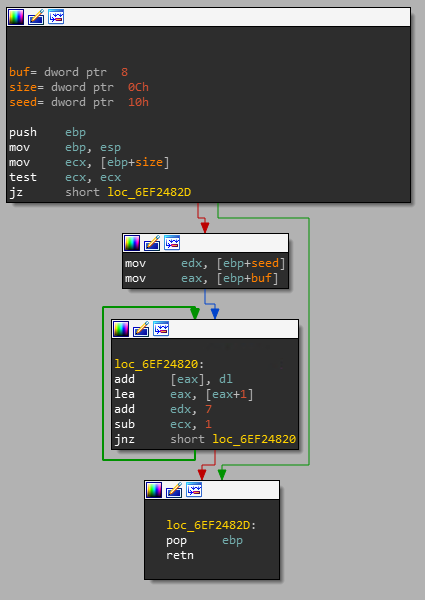

The picture below is a screenshot of IDA which shows the disassemby of the encryption subroutine.

Which translates more or less to the following decompiled C code:

/**

* Encrypt the data stored in buf, byte by byte

*/

void encrypt(char *buf, size_t size, int seed)

{

size_t remaining = size; // ecx register

int x; // edx register

//mov ecx, [ebp+size]

//test ecx, ecx

//jz short loc_6EF2482D

if(!remaining) {

return;

}

//mov edx, [ebp+seed]

x = seed;

do

{

//add [eax], dl

//lea eax, [eax+1]

*buf++ += x;

//add edx, 7

x += 7;

//sub ecx, 1

--remaining;

}

//jnz short loc_6EF24820 ; The Z bit is set by the sub instruction

while(remaining);

}

This function has an internal state which is initialized with the seed parameter. The encryption is done simply by adding the lower 8 bits of the internal state to every byte of the input data, letting the number overflow. The addition is done byte by byte and the state is incremented by 7 at every iteration.

Obviously, the function to decrypt the data is exactly the same as this one, but instead of adding the state, it is removed from each data byte.

Clearly, this is a ridiculously weak way of protecting data. Knowing the initial 8-bit seed is enough to decipher all the data. However this is not even necessary, since a bruteforce attack is very feasible! Let me explain.

Let's imagine that the original data is the string "Helloworld." which in would correspond to the following hex string

0x48 0x65 0x6C 0x6C 0x6F 0x77 0x6F 0x72 0x6C 0x64 0x2E

Now let's apply the encryption algorithm by choosing 0x49 as the seed. The data would become:

0x48 + 0x49 = 0x91

0x65 + 0x50 = 0xB5

0x6C + 0x57 = 0xC3

0x6C + 0x5E = 0xCA

0x6F + 0x65 = 0xD4

0x77 + 0x6C = 0xE3

0x6F + 0x73 = 0xE2

0x72 + 0x7A = 0xEC

0x6C + 0x81 = 0xED

0x64 + 0x88 = 0xEC

0x2E + 0x8F = 0xBD

As you can see, this cipher converts two equal characters into different bytes, due to the internal state being updated at every step. This reminded me a little bit of the inner workings of the WW-II Enigma Machine. Also, it is interesting to note that two different characters can translate to the same byte, as it happened in this example.

Let's consider now that we have the previous knowledge that every data record ends with a '.' which is actually pretty similar to the approach used by A. Turing to crack the WW-II Enigma. Given this information, we can say that the last byte 0xBD must convert to 0x2E, which is the ascii code for '.'

Therefore the internal state at that point is 0xBD - 0x2E = 0x8F.

Now, to obtain the seed it is sufficient to subtract 7 for every byte all the way up to the beginning of the data. i.e. subtract 7 * (size-1) = 70 = 0x46.0x8F - 0x46 = 0x49 which (surprise!) is the seed used for this example.

Bruteforce approach to decrypt the data

The method above will give you access to the decrypted data at the first try. However, since the encryption is done byte by byte, the possible values for the initial seed are only 256, which is a reasonable number of attempts for a bruteforce attack.

In addition to that, one could add other checks to filer out bad seed guesses, such as checking that all output bytes are within the range of printable ASCII characters.

Below is a simple python script that implements what I just described

#!/usr/bin/env python3

enc = [ 0x91, 0xB5, 0xC3, 0xCA, 0xD4, 0xE3, 0xE2, 0xEC, 0xED, 0xEC, 0xBD ]

def decrypt_ascii(in_data, seed):

ret = in_data[:]

for i, d in enumerate(in_data):

d -= seed

if d < 32 or d > 127:

return None

ret[i] = d

seed += 7

return ret

for seed in range(0, 0xFF):

data = decrypt_ascii(enc, seed)

if data:

print(str(seed)+': '+''.join(chr(i) for i in data))

Below I put the output of the script. It generated only 22 (out of a total of 256) outputs which are in the range of ASCII characters, and the "Helloworld." text can be easily spotted. Considering that a longer text would cause this filter to be more effective, one can conclude that bruteforce is in fact feasible.

66: Olssv~vysk5

67: Nkrru}uxrj4

68: Mjqqt|twqi3

69: Lipps{svph2

70: Khoorzruog1

71: Jgnnqyqtnf0

72: Ifmmpxpsme/

73: Helloworld.

74: Gdkknvnqkc-

75: Fcjjmumpjb,

76: Ebiiltloia+

77: Dahhksknh`*

78: C`ggjrjmg_)

79: B_ffiqilf^(

80: A^eehphke]'

81: @]ddgogjd\&

82: ?\ccfnfic[%

83: >[bbemehbZ$

84: =ZaadldgaY#

85: <Y``ckcf`X"

86: ;X__bjbe_W!

87: :W^^aiad^V

2. Patching a binary

In order to better understand how software licensing can be implemented, in the past I tried to patch an executable so that the license check is skipped.

I need to say that I did so only for research purposes, that I have a regular license for the software I studied and that I never did and never will release the patch for that software.

As I did in the previously described project related to file format reverse engineering, I'm using IDA freeware as a tool to help me with the disassembly of the x86 machine code in the binary file.

First dead end

One of the very first functions that came to my attention was very promising.

It seemed like that it returns 0 if the license is not valid, while it returns 1 if the license is valid.

These instructions appear at the very beginning of the function:

movsx eax, word_600A86C0

test eax, eax

jl short loc_6004873D

which basically translates to C to something like the following, given the fact that loc_6004873D corresponds to the end of the function:

if (word_600A86C0 >= 0) {

return word_600A86C0;

}

word_600A86C0 is a flag that is initialized in the .data section of the binary to 0xFFFF, which is -1 (two's complement).

This flag is set to either 0 or 1 by the logic of another function (maybe the function checking for the validity of the license?) and acts as a cache so that if the function is called multiple times, the return value is computed only once, stored in this variable and returned immediately in subsequent calls of the function.

At this point, my idea was to simply change the .data section of the binary and replace the 0xFFFF with a 0x0001. This way the function that sets this value would never be called and everything would behave as if that function did execute and returned 1.

I opened up my hex editor and quickly changed those two bytes from FF FF to 01 00.

That unfortunately did not work. However, one thing changed: the message related to the invalid license was no longer printed to the screen, but everything else (including the software protection mechanism) worked as intended. This meant that it was a dead end and that I needed to continue analyzing the assembly code.

Second attempt

I then decided to look at the application exit code returned to the operating system after this patch. It was '10', which is the same exit code returned when the unpatched binary was executed. I therefore focused my attention to the point where the function described above was being called, and in particular to the branch that the execution takes when 0 is returned:

mov eax, dword_600c4844

and eax, 0FFFFFFFEh

mov dword_600c4844, eax

which translates to the following C code:

dword_600c4844 &= 0xFFFFFFFE

This means that the last bit of the dword_600c4844 bitmask is cleared (set to 0). I then found a piece of code that checks if this last bit is set:

mov eax, dword_600c4844

and eax, 1

jnz short loc_600490DF

mov eax, 0Ah

jmp loc_6004A9C4

loc_6004A9C4 is the end of the function. 0x0A is 10 in decimal, which is the exit code in case of a license error. The reason why the initial attempt failed is that the last bit of the bitmask is never set. The new idea here was to either skip the check of the bit or set the bit.

By changing the x86 opcode from 0x75 to 0xEB, the jnz becomes an unconditional jump jmp, like so:

jmp short loc_600490DF

...and that did the trick. :)

To sum up, I patched the initial value of word_600A86C0 from FF FF to 01 00 in order not to display the error message related to the license and then patched the jump instruction (75 -> EB) so that it ignored the result of the check of the bitmask. If I only patched the jnz instruction, the patch would still work, however the error message would always appear.

Other patching ideas

Another way of patching the binary would be to avoid the call to the previously described function and directly set the last bit of the bitmask instead. Let's have a look at that portion of the disassembly code:

loc_60048A32:

lea ecx, [ebp+var_448]

push ecx

call sub_60048720

add esp, 4

test eax, eax

jnz short loc_60048A61

lea edx, [ebp+var_448]

push edx

call sub_600356A0

add esp, 4

mov eax, dword_600c4844

and eax, 0FFFFFFFEh

mov dword_600c4844, eax

loc_60048A61:

...

The idea is to insert the instructions to set the dword_600c4844 to 0x00000001 (maybe other bits have interesting meaning...) by replacing the first few instructions and then insert a NOP slide in order to preserve the original size of the binary. The opcode of the NOP instruction is 0x90. One way to set dword_600c4844 to 1 could be the following:

xor eax, eax

inc eax

mov dword_600c4844, eax

And this worked too :P

Conclusion

I'm sure that there are a lot of other ways to patch this binary in order to bypass the check, and this highlights my goal which is to show how easy it is to change the behaviour of a piece of software. The licensing system can be extremely complex, but most of the times (I would guess) it comes down to changing the few instructions that process the output of the license check, which is just a boolean value.

The only way to prevent binary patching is to require the execution of signed code, which is what's been done with smartphone apps. However computers where born a long time ago, when this kind of software security wasn't the priority. For backward compatibility, execution of unsigned code is still possible to this day on many platforms.

3. Curious aspects

Setting a register to 0

To set the return value (eax register) to zero, compilers usually optimize it like this:

xor eax, eax | 33 C0

In case you want to set it to 1:

xor eax, eax | 33 C0

inc eax | 40

The compiler does this instead of a mov instruction because the opcodes are shorter, as can be seen here:

mov eax, 0 | B8 00 00 00 00

The hex digits next to each instruction represent the raw assembly bytes. In the first two implementations the code needs 2 or 3 bytes of memory, while the mov instruction requires 5 bytes.